Endpoint Security , Incident & Breach Response , Managed Detection & Response (MDR)

Leak Reveals CIA 'CherryBlossom' Program Targeting Routers

WikiLeaks Dump Describes Custom Linux Firmware to Pwn Widely Used Routers

A new dump from WikiLeaks has revealed an apparent CIA project - code named "CherryBlossom" - that since 2007 has used customized, Linux-based firmware covertly installed on business and home routers to monitor internet traffic and as a stepping stone for exploiting targets' devices.

See Also: Global Password Security Report

Details of the CherryBlossom project were published Thursday by secrets-spilling organization WikiLeaks, as part of its ongoing series of "Vault 7" dumps of apparent CIA attack tools.

Previously leaked Vault 7 information, which dated from 2013 to 2016, described programs with such names as AfterMidnight, Athena, Dark Matter, Grasshopper, Hive, Pandemic and Weeping Angel. The identity of whoever leaked the information to WikiLeaks - and their motivation - remains unknown (see 7 Facts: 'Vault 7' CIA Hacking Tool Dump by WikiLeaks).

No Source Code

Unlike the "Equation Group" leaks of alleged NSA attack tools by the Shadow Brokers, the Vault 7 releases by WikiLeaks, including CherryBlossom, contain no source code or executable binaries. As a result, attackers cannot use the exploits referenced in the leak. But the leaked documentation does include indicators of compromise. As a result, as noted by the security researcher who tweets under the handle x0rz, potential victims can now scan their networks, as well as historical logs, for signs that they may have been exploited via CherryBlossom.

Someone should probably scan the Internet for CherryWeb folders #Vault7 #Wikileaks #CherryBlossom pic.twitter.com/u4nXtUQK8S

— x0rz (@x0rz) June 15, 2017

What's the Risk?

Despite the existence of a covert CIA router-infection program that's been operating since 2007, many security experts say the risk posed to the vast majority of non-U.S. citizens remains very low. Instead, they warn that numerous routers remain so poorly secured and rarely updated that anyone - cybercrime gang, bored teenager or nation state - could compromise them with little trouble.

Indeed, the Mirai malware that sprang up last year targeted default credentials in dozens of different types of internet of things devices built by numerous manufacturers. Mirai's success was directly proportional to the quantity of poorly secured routers that it was able to compromise (see Free Source Code Hacks IoT Devices to Build DDoS Army).

Many routers have known access credentials, notes Jake Williams, a cybersecurity consultant, exploit development instructor for SANS Institute, and former NSA employee. As a result, without needing to develop or load custom firmware, any attacker could access such devices to alter their DNS settings and launch man-in-the-middle attacks against users who connect to the devices, Williams notes via Twitter.

Instead, you should be worried about someone logging in and changing DNS settings. Instant MITM, no firmware mods. 2/2

— Jake Williams (@MalwareJake) June 15, 2017

Cybercriminals, for example, cooked up DNSChanger malware to alter domain name settings on PCs and redirect users to rogue DNS servers. While that malware was created to commit "advertising replacement fraud" - and click fraud - attackers could have easily logged, stored or manipulated traffic flowing to or from compromised devices or infected routers as part of their campaign.

User Guide to CherryBlossom

Starting in 2007, however, the CherryBlossom project was designed to infect wireless routers and access points with custom-built firmware, which could allow the devices to be used as man-in-the-middle attack points against targets of interest.

The 175-page CherryBlossom user manual, which includes a "secret" classification, notes that "as of August 2012, CB-implanted firmwares can be built for roughly 25 different devices from 10 different manufacturers (including Asus, Belkin, Buffalo, Dell, Dlink, Linksys, Motorola, Netgear, Senao, and US Robotics)." The manual, dated 2012, says the program has been running since 2007.

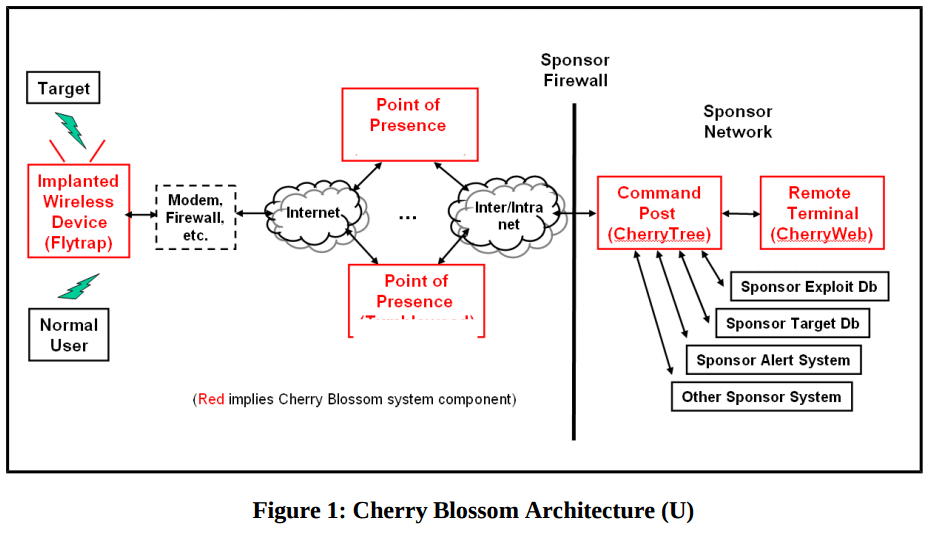

"The Cherry Blossom (CB) system provides a means of monitoring the internet activity of and performing software exploits on targets of interest. In particular, CB is focused on compromising wireless networking devices, such as wireless (802.11) routers and access points (APs), to achieve these goals," the manual reads.

WikiLeaks notes in an overview that accompanies the CherryBlossom document dump that "by altering the data stream between the user and internet services, the infected device can inject malicious content into the stream to exploit vulnerabilities in applications or the operating system on the computer of the targeted user."

WikiLeaks says the CIA developed and implemented CherryBlossom with the help of Stanford Research Institute, aka SRI International, which is an independent, nonprofit Silicon Valley research center. SRI International couldn't be immediately reached for comment.

Forcing Wireless Firmware Updates

Custom CherryBlossom firmware can be installed on targeted devices using a variety of techniques, according to the user guide, including connecting via a LAN or wireless LAN. The guide adds that for routers that do not allow wireless users to update firmware, special exploitation tools have been developed that force the routers to do so anyway.

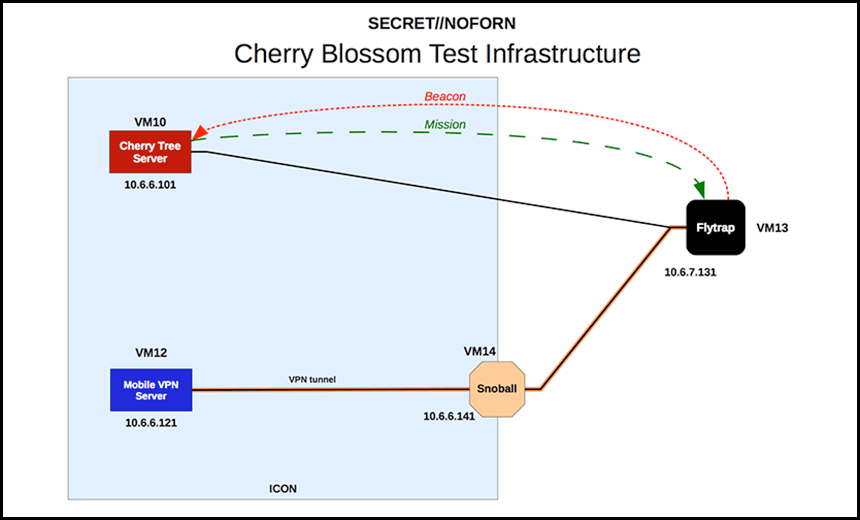

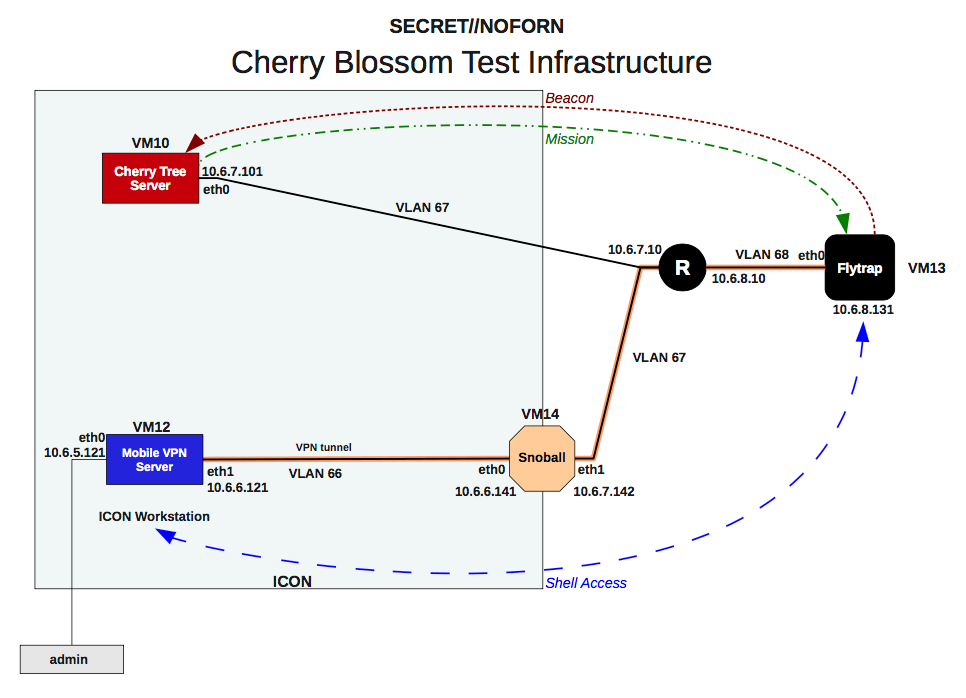

After the firmware gets installed and the device reboots, the documentation refers to the device as a FlyTrap, and notes that it will "beacon" to a command-and-control server, called the CherryTree, at preset intervals, or to alert the administrator when specified events occur. Those communications get routed through a point of presence, aka Snowball.

The CherryTree can then send a mission, as specified by an operator, back to the FlyTrap. Operators can manage these missions, issue new ones and view results via a browser-based user interface - dubbed CherryWeb. Various tasks can be assigned - for example, to scan for specific email addresses and copy all traffic going to or from that address.

The user guide notes that all data - except for intercepted network traffic - exfiltrated via the FlyTrap is encrypted and disguised as an HTTP cookie for an image file. After the FlyTrap sends the exfiltrated data, the CherryTree responds by sending a binary image file, again to make the covert communication appear to be legitimate.