DDoS Protection , Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development , Security Operations

Cybercrime-as-a-Service Economy: Stronger Than Ever

Available Now: DDoS on Demand, Bitcoin Tumblers, Attack Affiliates and More

The cybercrime sector involves a rapidly growing services economy.

See Also: Rising IoT Botnets and Shifting Ransomware Escalate Enterprise Risk

Police estimate that just 100 to 200 people may be powering the "cybercrime-as-a-service" ecosystem by developing the attack code and services that enable criminals who lack technical acumen to pay for their cybercrime will to be accomplished.

If you can think of a cybercrime service, chances are that it exists.

Security experts say various providers offer such services as installing malware onto PCs and then selling access to those devices; selling subscriptions to malware and ransomware toolkits that automate attacks, with developers taking a cut of all proceeds; and "mule" services that will arm gang members with fake debit cards so they can make as many ATM cash withdrawals as possible before banks catch on.

Some service providers offer bulletproof hosting services, promising to look the other way should the rented servers be used to launch malware attacks. Other services will offer to "clean" the bitcoins that attackers demand from victims, making them more difficult for authorities to trace.

Many cyber-extortion attacks today, meanwhile, involve criminals threatening to launch distributed denial-of-service attacks against organizations unless they pay attackers bitcoins. To carry through on those threats, attackers often rely on so-called booter or stresser services, which sell on-demand DDoS attacks. This week, police in Israel - at the request of the FBI - arrested two men who have been accused of running a stresser/booter service called vDos. The service earned an estimated $600,000 in profit over the past two years as a result of launching 150,000 on-demand disruptions.

Based on online advertisements, the cybercrime-for-hire business appears to be so lucrative and booming that hacker gangs can't keep their crews staffed.

Why Criminals Love Ransomware

That's especially true for ransomware attacks, which criminals love because - as a recent report from McAfee summarizes - "they're financially lucrative with little chance of arrest."

Some ransomware gangs have even set up "customer care centers" to field ransomware victims' inquiries, for example, instructing them in how to procure the bitcoins attackers demand in exchange for a decryption key for unlocking a forcibly encrypted PC or server.

At the end of last year, the number of new ransomware samples seen in the wild spiked. McAfee says that was driven, in part, by the emergence of open source ransomware code such as EDA2 and Hidden Tear, both of which were created for what their developers claimed were educational purposes. Both, however, quickly found their way into cybercriminals' arsenals.

Last month, for example, a strain of ransomware that's based on Hidden Tear and sports a Pokémon Go theme was discovered by MalwareHunterTeam member Michael Gillespie. Still, the developers of those open source options may be having the last laugh, since they've subsequently disclosed purposeful weaknesses in the code, designed to make related ransomware easy to decrypt.

Ransomware's Surge

Unfortunately, not all ransomware is built with flawed crypto; options abound. In the first half of this year, Trend Micro reported seeing 79 new ransomware families, compared to 29 new ransomware families in all of 2015.

Ransomware is in vogue because related attacks are "very easy for criminals to monetize," says Rik Ferguson, vice president of security research for Trend Micro. "And it's something which is very easy for them to recruit in terms of networks, affiliates and distribution. And it's something which is morphing into another one of those crime-as-a-service offerings."

One affiliate program called Atom, for example, is based on Shark ransomware, which now "offers the soon-to-be cybercriminal customer an attractive 80 percent share of the profit for every successful payment from ransomware victims," Rommel Joven, an anti-virus analyst for cybersecurity software and hardware vendor Fortinet, says in a blog post.

Operational Security Concerns

Some attackers leverage these ransomware-as-a-service offerings - other examples include Ransom32 and Encryptor - not just because they eliminate the need to maintain their own attack infrastructure or code, but also because they can facilitate better operational security.

"You can use someone else's infrastructure, and so you're putting another layer between you and ... the defenders or law enforcement that might try to detect you," says Rick Holland, vice president of strategy for Digital Shadows.

Operational security - a.k.a. OPSEC - refers to the practice of making one's activities more difficult to trace. For criminals, that might include using VPN service providers, the Tor anonymizing browser as well as bitcoins, which offer the promise of getting paid via tough-to-trace transactions.

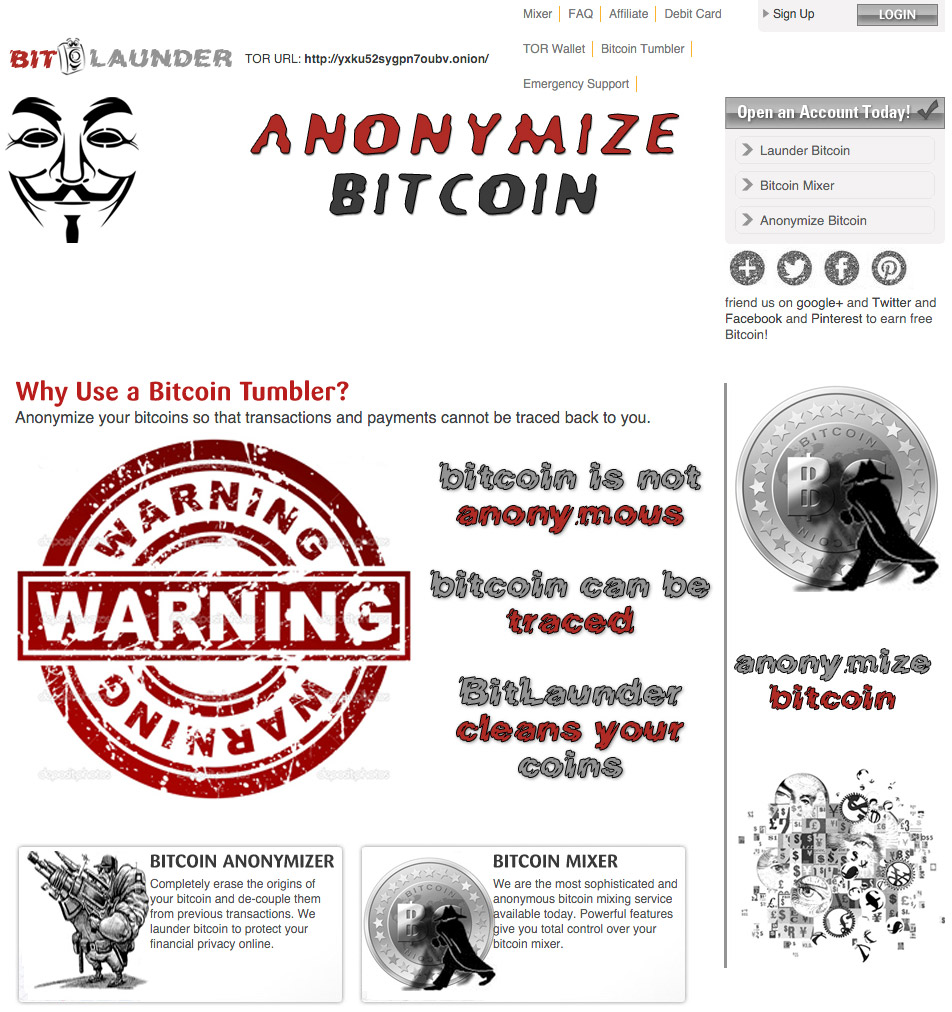

Bitcoin Tumblers

Bitcoins, however, aren't truly anonymous, but rather pseudonymous, and researchers reportedly continue to find and develop new tools that allow law enforcement agencies to correlate information about suspects with bitcoin transactions, which all get logged, courtesy of the blockchain. What those actual capabilities are today, however, remains a closely held secret.

In response, some criminals have taken to seeking "clean coins" by means of a process called tumbling, which is the process of using a third-party service or technology to launder bitcoins. This "bitcoin mixing," as it's also known, involves breaking "the connection between a bitcoin address sending coins and the address(es) they are sent to," security researcher Will Gragido said in a blog post written for Digital Shadows.

"Tumbling, it was discovered, could be as easy as confusing the trail of transactions between two wallets, making investigation and attribution almost impossible," he said. For example, an attacker could create one wallet, add bitcoins to it, then create a second wallet - via Tor - and move the funds into the new wallet.

For some attackers, however, the preferred option appears to be using third-party services to provide tumbling, which promise even greater degrees of obfuscation. One such service, Helix, promises users added privacy and security by swapping customers' bitcoins for "brand new ones that have never been to the darknet before."

As with all things cybercrime, where there's a criminal need, service providers seem all too ready to fulfill it.